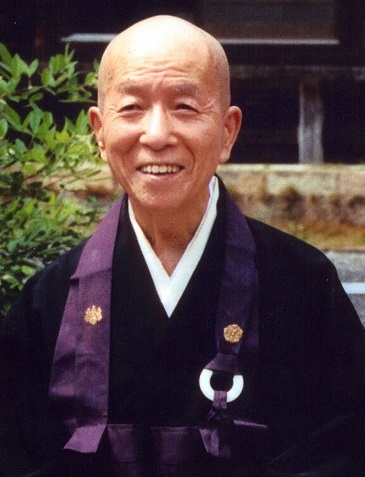

Zen Master Dogen

About Dogen Zenji

Zen Master Dogen Quotes

(Taken from Prof. Masunaga book 'Soto Approach to Zen', the chapter: 'The place of Dogen', pages 203-214)

The place of Dogen

It was Dogen (1200-1253) who first brought Soto Zen to Japan. Keizan (1268-1325) made possible the popularization of Soto Zen, thereby laying the foundation for the large religious organization, which it is today. Dogen, born in a noble family, quickly learned the meaning of the Buddhist word 'mujo' (impermanence). While still young, he lost both his parents. He decided then to become a Buddhist priest and search for truth. He went first to Mt. Hiei, the headquarters of the sect.

The true dharma eye: Zen Master Dogen’s three hundred koans / with commentary and verse by John Daido Loori; translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi and John Daido Loori. EISBN 978-0-8348-2311-2 ISBN 978-1-59030-465-5 (hardcover: alk. Paper) ISBN 978-1-59030-465-5 (paperback) 1. Koan—Early works to 1800. Loori, John Daido. Born in the year 1200 Dogan Zenji was a Japanese Buddhist monk, writer, poet and philosopher. He was the founder of the Soto school of Zen in Japan. Below are his best quotes revolving around the subjects of peace, love and harmony. Share these Dogan quotes. Dogen then met master Eisai, recently returned from China, who taught Rinzai Zen: En el templo de Kennin-ji he became disciple of Myozen, the succesor to Eisai. Even though the school did not completely satisfy him, Dogen was able to practice deeply and he developed his interest for Zen practice.

Zen Master Dogen Quotes

At the young age he was assailed by the following doubt Both the esoteric and external doctrines of the Buddha teach that enlightenment is inherent in all beings from the outset. If this is so, why do all the Buddhas, past, present, and future, seek enlightenment?

This doubt, clearly pointing to the dualistic contradiction between the ideal and the actual, is the kind of anguish likely to arise in the mind of any deeply religious person. Unable to resolve this great doubt at Mt. Hiei, Dogen decided to study Buddhism under Eisai (1141- 1215). For some time he practiced Zen meditation with Eisai's disciple, Myozen. Then at the age of 24 Dogen accompanied by Myozen, embarked on a dangerous voyage to China in search of the highest truth of Buddhism. There he visited all of the well-known monasteries, finally becoming a disciple of Ju-tsing (J. Nyojo) who was living on Mt. Tien-tung (J. Tendo). For two years Dogen studied hard day and night and at last realized liberation of body and mind - the most important event of one's life.

- Moon in a Dewdrop Writings of Zen Master Dogen By: Kathleen (Shokai) Bishop, MS, PhD 2018 I hope you will spend some time working with the wonderful wisdom of Eihei Dogen who was born in A.D. Although he was born in Japan and studied there he ventured into China to study Buddhism as well.

- While each of these styles is commonly taught today, Master Dogen recommended only Kekkafuza and Hankafuza. In his book Three Pillars of Zen, Philip Kapleau says that practitioners in the Rinzai school face in, towards each other with their backs to the wall, and in the Sōtō school, practitioners face the wall or a curtain.

Dogen freed himself from the illusion of the ego, the result of dualistic thinking and he experienced deeply the bliss of Buddhist truth. He continued his religious training in China for two years before returning to Japan at the age of 28.

Dogen's greatest desire was to spread the Buddhist religion and thereby benefit all mankind. He first settled in Kosho Temple where he trained Zen monks. He had a Zen training hall (Dojo) built and lectured before both the Buddhist clergy and laity for more than 10 years. In 1243, at the urging of Hatano Yoshishige, he moved to Echizen, now Fukui Prefecture, and founded the Eihei Temple, which today is one of the two head temples of the Soto sect. Burning with enthusiasm to teach true Buddhism to all seekers, he spent some 10 years there leading quiet religious life.

Dogen is the greatest religious figure and creative thinker in's Japanese history. Thoughtful leaders outside the Soto sect have declared that the essence of Japanese culture cannot be correctly understood without considering this great Zen master. Deeply impressed at the thoroughness and depth of Dogen's thought, many Japanese have gained new confidence in the potentialities of their culture.

Dogen enjoys such high regard because his Philosophy, religion, and Personality blend with the ideals held by humanity throughout history. His ideas are universally applicable. Dogen's greatness rests on three Points: his profundity his practicality, and his nobility. His principal work, Shobogenzo, in 95 chapters, is a true masterpiece; it clearly reveals his thought and faith. Instead of writing in classical Chinese, so popular in those days, Dogen used Japanese so that every one will be able to read it. His style is concise and to the point. His thought is noble and profound. His sharp logic and deep insight not only put him at the forefront of Japanese thought, but also give him an important Place in modern philosophy. Because of these features the standpoint of Dogen provide a base for synthesizing Oriental and Occidental thought.

But Dogen's significance is not found merely in the excellence of his theories. We should always remember that Dogen never amuses him self with empty words and barren phrases divorced from reality. In Dogen's writings we find theory and practice, knowledge and action, inseparably entwined. The detailed Zen regulations found in Dogen's Eihei Daishingi established this fact very clearly.

Buddhism teaches us that we must awaken our own body and mind thoroughly and experience them fully. This does not mean mere intellectual knowledge but living the life of the Buddha without strain. Dogen combined both deep insight and thorough practice in his character- and therein lies his greatness.

Contemporary Value of Dogen

What is the basic thought and belief of Dogen?

- The essence of Dogen's teaching lies, first of all, in the correct transmission of a united Buddhism He felt that if the Zen sect formed its own system in contrast to those of other sects, it was apt to become one-sided and biased. So Dogen rejected the name 'Zen sect' as indicating something distinct from the other sects.

Those who use the name Zen sect to describe the great way of the Buddhas and patriarchs,

he says,have not yet seen the way of the Buddha.

To Dogen the establishment of the five sects of Zen only destroyed the unity of Buddhism. He considered it a product of shallow- thinking. Dogen sought to restore sectarian Sung Dynasty Zen to the main road of Buddhism from which it had stranded and to enable Chinese Buddhism, which had deviated from the main course, to find itself again. - Dogen, who was free from egotism and vain desires for wealth and fame, rejected the Buddhism of his period as imperfect. It goes without saying that in selecting the doctrines of Buddhism to be spread throughout the land, the time, place, and persons to receive the doctrine must be taken into consideration. The division of the teachings of Buddhism into three periods (the period of the True Law, the period of the imitation of the True Law, and the period of the decline of the True Law) is nothing but a means for explaining the changes in Buddhist philosophy to the masses. In Dogen's view it is precisely because we are now in the period of decline that we must make unrelenting efforts to live in the spirit of the Buddha and to grasp the essence of Buddhism directly. Therefore Dogen says:

If you do not enter Buddhism in this life on the pretext that we are in a period of decline and unable to know truth, then in which life will you realize truth?

Dogen discovered deep meaning in the efforts of men to discover eternal truths in their own character. We can observe here Dogen's intense resistance to religious fatalism and Mappo (the last of the three periods mentioned above) thought. If one has fervor for truth, the limitations of time and place can be transcended, and one can see the Buddhas and patriarchs directly. This is because the three periods are not periods in time but really stages in the development of men. For Dogen the object of adoration is the historical Buddha who unites the three aspects in his own personality. This object, the Buddha, is source of our teaching and the guarantor of our belief. At the conclusion of the Sokushinjebutus, Dogen writes,

The phrase 'all the Buddhas' denotes Sakyamuni Buddha. The heart of Sakyamuni is Buddhahood itself. All the Buddhas who appeared in the past, appear in the present, and will appear in the future must inevitably be Sakyamuni.

In Buddhist doctrine we often come across such Buddhas as Amitayus, Mahavairocana, and others. However, these are only manifestations Sakyamuni Buddha. As Buddhist thought developed and expanded, many others- likewise attained enlightenment. Both Mahayana and Hinayana consider the origin of Buddhism to be in Buddhagaya (where the Buddha attained enlightenment). We may, therefore, say that the object of Dogen's adoration is Sakyamuni Buddha who attained enlightenment under the Bodhi-tree in Buddhagaya and who is the model for all Buddhas. He is neither a Buddha conjured up in the imagination, nor an idealized Buddha a devoid of a real personality, but an actual historical personage. Later generations viewed the nature (body) of a Buddha from three different angles. 1) The Body of the Law (Skt. - Dharmakaya), which is a personification of the True Laws of the Universe and hence transcends all finite limitations. 2) The Body of Retribution (Skt - Sambhogakaya) which is the reword for all training undertaken before enlightenment, and 3) The Body of Transformation (Skt.- Nirmanakaya) which comes into being so that the Buddha may adopt himself to varying individualities and capacities.The Buddha of the Soto sect transcends this division. He is the historical Buddha who unites the three aspects in his own personality. He is termed in the Soto sect

Daion Kyoshu Honshi Shakamuni Butsu Daiosho,

which many be translatedThe great Benefactor, the Founder of the Religion, Original Teacher, Sakyamuni Buddha the Great Monk.

This great monk is beyond comparison and has a unique historical personality. Dogen strongly rejected the one-sided sectarian Buddhism that ignores the mainstream and clings to trivial. He taught a fully integrated Buddhism which existed before the division into Hinayana or Mahayana. Accordingly, the objected of adoration is Sakyamuni, the founder of the religion, who naturally predates any splits in dogma. The uninterrupted transmission of the True Life starting from the Buddha is what we callShoden no buppo

orcorrectly transmitted Buddhism.

Now we must ask ourselves the question,

How did the Buddha find the way to live in truth?

The answer has already been given above: though zazen Dogen writes in Bendowa, a chapter of the Shobogenzo,The teacher Sakyamuni handed down this unexcelled method of enlightenment. And the Tathagatas of the past present, and future and the patriarchs in India and China have also attained enlightenment through zazen.

Thus beginning with the historic Buddha, all the patriarchs and masters have experienced enlightenment through zazen. At the time of his enlightenment, the Buddha is said to have declared:Together with me the Great Earth and all beings have become enlightened. The grass, the trees, the very soil have achieved Buddhahood.

Mankind was saved by the enlightenment of the Buddha. So in Dogen's view there is absolutely no need for us to practice asceticism by imitating Buddha. In Gakudo Yojinshu, he says,Those who practice the way of the Buddha must first have faith in the way of the Buddha. This means to believe that we are in enlightenment already and have neither illusion nor error.

We are already on the path to enlightenment and are filled with the wisdom of the Buddha. Bodhidharma, the First Patriarch of Chinese Zen, said:We deeply believe in accordance with the teachings of our master that all mankind is endowed with an identical Buddha-nature.

Our true nature reveals it self only when we have thoroughly understood the doctrine of the non-existence of the ego.Human beings real nature is what we call the Buddha Mind or Buddha-nature. Bodhidharma taught us to believe that all mankind is endowed with this nature inherently. In the Soto sect, belief in this nature is called

honsho no anjin

(Tranquil mind of original enlightenment). Since we are in a state of enlightenment from the outset, zazen cannot he regarded as a means to achieve enlightenment. In the Soto sect zazen is not a way leading to enlightenment, but a religious practice carried on in a state of enlightenment. This zazen differs from the meditation practiced by the Buddha before his enlightenment. It corresponds rather to the Jijiyu Zammai (self- joyous meditation) practiced after the enlightenment of the Buddha. In this zazen one fully experiences the bliss of enlightenment by oneself.Zazen itself, we may say, is Buddhahood. Since zazen is the practice of the Buddha, those who engage in it are Buddhas. Zazen, which is based upon the peaceful state of mind arising from original enlightenment, is also termed

wonderful practice.

We view this wonderful practice and enlightenment as one and the same thing. Dogen says of this in Bendowa,In Buddhism training and enlightenment are the same. Be cause this is training enfolding enlightenment, the training even at the outset is all of enlightenment.

- This is what we describe as the identity of original enlightenment and wondrous training. Although we do not deny the existence of practice and enlightenment, we say that one must not cling to those concepts. This non-attachment we call untainted enlightenment and practice. It is correctly transmitted Buddhism and is characterized by the harmony, not opposition, of enlightenment and practice. Some may ask, since enlightenment and practice are one, isn't zazen superfluous? To this we must answer in the negative. It is easy to fall into such erroneous thinking about zazen. Dogen says in the Zuimonki,My idea of the untainted man of religion is the person who gives himself completely to Buddhism and leads a religious life without troubling himself about the attainment of enlightenment.

If we devote ourselves whole heartily to Buddhism without any desire to reach enlightenment, we became the living embodiment of Buddhism.- Zazen is the basic expression of a religion that emphasizes practice. Once its foundation is firmly laid, it becomes an activity of the Buddha adaptable to our daily life. Since it is a practice resting on enlightenment, it will transform our daily life into a religious one and reveal our tranquil mind of original enlightenment.

Prof. Masunaga Reiho about Dogen

Taken from Prof. Masunaga Reiho book: Zen Beyond Zen

Dogen profoundly expressed the essence of Zen. In his biography it is said that Dogen had great doubts about reality and ideals when he was 15 years old, and he visited Eisai in an effort to solve this problem. Dogen later studied under Myozen, a disciple of Eisai. When he was 24, Dogen went to China with Myozen to study Zen. In 1225 he visited Ch'ang-weng Ju-tsing (1163-1228) at Keitoku temple in Mt.Tenndo; Deeply impressed, he trained hard. Finally he freed himself from dualistic attachment to body and mind and received the master's approval. At that time he was 26 years old. He trained himself after enlightenment for two years and in the spring of 1228, he was given a book of genealogy testifying to his grasp of true Zen. After his return to Japan he made Kyoto the center of his activities and concentrated on writing, and meditation, in Koshoji at Uji and taught priests and laymen who visited him. Then, in July of 1243, when he was 44 he moved to the mountains of Echizen and built the temple Eiheiji. Here he lived a calm life of meditation for about 10 years.

Dogen's uniqueness consists in his unifying and demonstrating deep philosophical thought and Thorough religious practice through his remarkable personality. Dogen shunned worldly fame and profit. He also steered clear of political authority. Foregoing a fancy Kesa, he wore a rough robe throughout his teaching life. He always stressed the way-seeking spirit, and he urged others to live each to the fullest. Dogen stood on quietude and original enlightenment. He considered cross-legged sitting superior training within original enlightenment. He devoted himself to thorough training day and night. He constantly lived a life of gratitude for the Buddha and the patriarchs.

Dogen's right law was handed down to Keizan Jokin through Koun Ejo and Tettsu Gikai. With these Zen teachers the Soto school begin making big impact on society. Linking itself with the common people, it spread throughout the entire nation. Many brilliant Zen masters emerged. The teachings of the school flourished especially in the Tokugawa Period. Gesshu, Manzan, and Baiho pressed for revival of tradition in the school.

| home |

thezensite: The Shōbōgenzō

The Shōbōgenzō (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye) is the master work of the Japanese Sōtō Zen Master Eihei Dōgen (1200 - 1253). It consists of a series of lectures or talks given to his monks as recorded by his head monk, Ejo, who became his Dharma successor although Dōgen was involved in the editing and recording of some of the Shōbōgenzō. This is the first major Buddhist philosophical work composed in the Japanese language.

There were only two complete English translations of the Shōbōgenzō previous to this version: Gudo Nishijima and Chodo Cross's Master Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō in four volumes (available from Windbell Publications) and Shobogenzo, The Eye and Treasury of the True Law, by Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens. There are many translations of sections of the Shōbōgenzō. There are also many commentaries on Dōgen and his work. A search on this website will uncover articles on Dōgen and his teachings.

The Gudo Nishijima and Chodo Cross's Master Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō in four volumes is now available for download for free from thezensite: Dogen Teachings page

The Complete Shōbōgenzō is available here (this site) and here from Shasta Abbey, translated by Rev. Hubert Nearman.

WARNING: the complete text is 1144 pages in .pdf and 8, 675 Kb. Not recommended for dial-up modems. If you have difficulty downloading this from this website, try the Shasta Abbey link. Below are links to each of the 96 chapters and other parts of the book. All pages are in .pdf format.

| Title Page | Cover Page |

| Dedication | Copyright |

| Glossary | Intoduction |

| Contents | About the Translator |

| Appendix of names | Acknowledgements |

Another translation is in progress and is available through Stanford University. This translation is part of the Soto Text Project. You can read about this project via the link. I've added links to the Stanford site of the translations that are complete. You will notice that some of the names of the chapters are different and the numbering is also different. However, I believe that for students of the Shōbōgenzō, it may be fruitful to compare different translations. Other chapters have been translated as well and I've added those available on the web in the third column. Note that most of these translations are off site and therefore the links may well die in time. Please let me know of any dead links. Thank you.

Other Translations | |

translated by: | |

| 1. Bendowa A Discourse on Doing One's Utmost in Practicing the Way of the Buddha | |

| 2. Makahannya-haramitsu On the Great Wisdom That Is Beyond Discriminatory Thought | |

| 3. Genjo Koan On the Spiritual Question as It Manifests Before Your Very Eyes | |

| 4. IkkaMyoju On 'The One Bright Pearl ' | |

| 5. Juundo-shiki On Conduct Appropriate for the Auxiliary Cloud Hall | |

| 6. Soku Shin Ze Butsu On 'Your Very Mind Is Buddha' | |

| 7. Senjo On Washing Yourself Clean | |

| 8. Keisei Sanshoku On 'The Rippling of a Valley Stream, the Contour of a Mountain' | |

| 9. Shoaku Makusa On 'Refrain from All Evil Whatsoever' | |

| 10. Raihai Tokuzui On ' Getting the Marrow by Doing Obeisance' | Stanley Weinstein |

| 11. Uji On 'Just for the Time Being, Just for a While, For the Whole of Time is the Whole of Existence' | Reiho Masunaga Dan Welch and Kazuaki Tanahashi Bob Myers (MsWord doc) |

| 12. Den'e On the Transmission of the Kesa | |

| 13. Sansui Kyo On the Spiritual Discourses of the Mountains and the Water | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 14.Busshō On Buddha Nature | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 15. Shisho On the Record of Transmission | |

| 16. Hokke Ten Hokke On 'The Flowering of the Dharma Sets the Dharma's Flowering in Motion' | |

| 17. Shin Fukatoku On 'The Mind Cannot Be Held Onto' (Oral version) including Translator's Addendum to Chapter 17 | |

| 18. Shin Fukatoku On 'The Mind Cannot Be Grasped' (Written version) | |

| 19. Kokyo On the Ancient Mirror | |

| 20. Kankin On Reading Scriptures | |

| 21. Bussho On Buddha Nature including Translator's Addendum to Chapter 21 | |

| 22. Gyobutsu Iigi On the Everyday Behavior of a Buddha Doing His Practice | |

| 23. Bukkyo On What the Buddha Taught | |

| 24. Jinzu On the Marvelous Spiritual Abilities | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 25. Daigo On the Great Realization | |

| 26.Zazen Shin Lancet of Zazen | |

| 27. Butsu Kojo Ji On Experiencing That Which Is Above and Beyond Buddhahood | |

| 28. Immo On That Which Comes Like This | |

| 29. Gyoji On Ceaseless Practice | |

| 30. Kaiin Zammai On 'The Meditative State That Bears the Seal of the Ocean' | |

| 31. Juki On Predicting Buddhahood | |

| 32. Kannon On Kannon, the Bodhisattva of Compassion including Translator's Addendum to Chapter 32 | |

| 33. Arakan On Arhat | Stanley Weinstein |

| 34. Hakujushi On the Cypress Tree | |

| 35. Komyo On the Brightness of the Light | |

| 36. Shinjin Gakudo On Learning the Way Through Body and Mind | |

| 37. Muchu Setsumu On a Vision Within a Vision and a Dream Within a Dream | |

| 38. Dotoku On Expressing What One Has Realized | |

| 39. Gabyo On ' A Picture of a Rice Cake' | |

| 40. Zenki On Functioning Fully | |

| 41. Sesshin Sessho Talking of the Mind, Talking of the Nature | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 42. Darani On Invocations: What We Offer to the Buddhas and Ancestors | |

| 43. Tsuki On the Moon as One's Excellent Nature | |

| 44. Kuge On the Flowering of the Unbounded | |

| 45. Kobusshin On What the Mind of an Old Buddha Is | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 46. Bodaisatta Shishobo On the Four Exemplary Acts of a Bodhisattva | |

| 47. Katto On The Vines That Entangle: the Vines That Embrace | |

| 48. Sangai Yuishin On 'The Threefold World Is Simply Your Mind' | |

| 49. Shoho Jisso On the Real Form of All Thoughts and Things | |

| 50. Bukkyo On Buddhist Scriptures | |

| 51. Butsudo On the Buddha's Way | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 52. Mitsugo On the Heart-to-Heart Language of Intimacy | |

| 53. Hossho On the True Nature of All Things | |

| 54. Mujo Seppo On the Dharma That Nonsentient Beings Express | |

| 55. Semmen On Washing Your Face | |

| 56. Zazengi On the Model for Doing Meditation | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 57. Baika On the Plum Blossom | |

| 58. Jippo On the Whole Universe in All Ten Directions | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 59. Kembutsu On Encountering Buddha | |

| 60. Henzan Extensive Study | |

| 61. Ganzei On the Eye of a Buddha | |

| 62. Kajo On Everyday Life | |

| 63. Ryugin On the Roar of a Dragon | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 64. Shunju On Spring and Autumn: Warming Up and Cooling Down | |

| 65. Soshi Seirai I On Why Our Ancestral Master Came from the West | |

| 66. Udonge On the Udumbara Blossom | |

| 67. Hotsu Mujo Shin On Giving Rise to the Unsurpassed Mind | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 68. Nyorai Zenshin On the Uni versal Body of the Tathagata | |

| 69. Zammai-o Zammai On the Meditative State That Is the Lord of Meditative States | |

| 70. Sanjushichihon Bodai Bumpo On the Thirty-Seven Methods of Training for Realizing Enlightenment | |

| 71. Temborin On Turning the Wheel of the Dharma | |

| 72. Jisho Zammai On the Meditative State of One's True Nature | |

| 73. Daishugyo On the Great Practice | |

| 74. Menju On Conferring the Face-to-Face Transmission | |

| 75. Koku On the Unbounded | |

| 76. Hatsu'u On a Monk's Bowl | |

| 77. Ango On the Summer Retreat | |

| 78. Tashintsu On Reading the Minds and Hearts of Others | Carl Bielefeldt |

| 79. O Saku Sendaba On 'The King Requests Something from Sindh' | |

| 80. Jikuin Mon On Instructions for Monks in the Kitchen Hall | |

| 81. Shukke On Leaving Home Life Behind | |

| 82. Shukke Kudoku On the Spiritual Merits of Leaving Home Life Behind | |

| 83. Jukai On Receiving the Precepts | |

| 84. Kesa Kudoku On the Spiritual Merits of the Kesa | |

| 85. Hotsu Bodai Shin On Giving Rise to the Enlightened Mind | |

| 86. Kuyo Shobutsu On Making Venerative Offerings to Buddhas | |

| 87. Kie Bupposo Ho On Taking Refuge in the Treasures of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha | |

| 88. Jinshin Inga On the Absolute Certainty of Cause and Effect | |

| 89. Sanji Go On Karmic Retribution in the Three Temporal Periods | |

| 90. Shime On The Four Horses | |

| 91. Shizen Biku On the Monk in the Fourth Meditative State | |

| 92. Ippyakuhachi Homyomon On the One Hundred and Eight Gates to What the Dharma Illumines | |

| 93. Shoji On Life and Death | |

| 94. Doshin On the Mind's Search for Truth | |

| 95. Yui Butsu Yo Butsu On 'Each Buddha on His Own, Together with All Buddhas' | |

| 96. Hachi Dainingaku On the Eight Realizations of a Great One |